Time to retool? Shifting strategy at the state’s big credit union raises debate over balancing member needs

Chris Ayer joined the North Carolina State Employees’ Credit Union in Raleigh as a software coder in 1988 after working for a Roanoke, Virginia, bank. His initial salary was about the same as his wife’s paycheck as a Wake County school teacher.

Ayer eventually became the credit union’s chief technology officer. But he says he didn’t realize why his job really mattered until receiving a call in 1999 from a member who wanted to know his account balance.

Credit union policy blocked IT staffers from sharing customer information, so Ayer mentioned other options. The guy wasn’t impressed, so Ayer urged him to walk into a local branch and talk with a teller.

I’m a quadriplegic, so that’s not an option, the member responded.

That’s when SECU’s culture of putting members first really hit him, Ayer recalls. If that meant driving to the member’s home and delivering the information personally, that’s what you did.

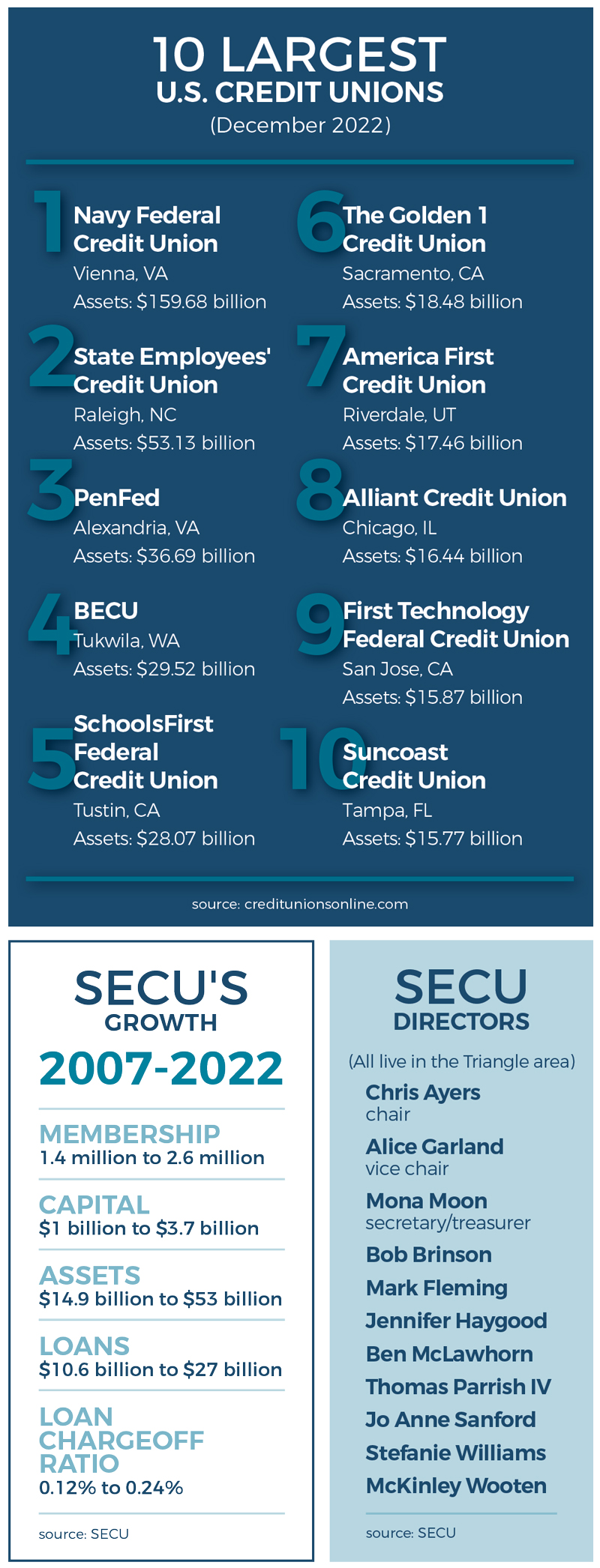

Seventeen people started SECU with $437 in 1937, when the U.S. was mired in depression. Today, it has $53 billion in assets and is the second-largest U.S. credit union. It has nearly 8,000 employees in 100 counties and 2.6 million members, or more than one in five North Carolinians.

No one disputes the credit union’s remarkable achievements. Now, though, how it operates is being challenged by insiders who say some of its distinctive policies need updating in a fast-changing sector. Like most change, it’s causing sparks, in this case from critics who say SECU is straying from its core mission.

SECU has never lost money in 85 years, booking a net gain of more than $1 billion over the last two fiscal years. It holds much more capital than required. Credit unions don’t have shareholders and are considered not-for-profit.

Three North Carolina megabanks — Bank of America, BB&T (now Truist), and First Union (renamed Wachovia, then Wells Fargo) — grew through hundreds of acquisitions, mostly out of state, engineered by aggressive CEOs. The dealmaking worked great, until it didn’t: Wachovia, BofA and BB&T received government bailouts after the late-2000s housing depression. Each bank repaid the money.

SECU stuck to internal growth, a unique consumer lending strategy and a culture that motivated good customer service.

The credit union’s inflection point is sparked by its unpaid, volunteer board of veteran state government leaders and Chief Executive Officer Jim Hayes, a veteran industry regulator and executive hired in 2021. During his 18 months on the job, Hayes has reorganized SECU’s senior leadership and is directing some fundamental changes rejected for decades by his predecessors.

A key thrust: The credit union should grow by lowering rates on loans to members with strong credit ratings, while also remaining highly focused on those with modest incomes. Four of five SECU members are not state employees, but rather family members or in private-sector jobs. About 16% of members’ total debt is with SECU, down from 26% five years ago and more than 30% a decade ago.

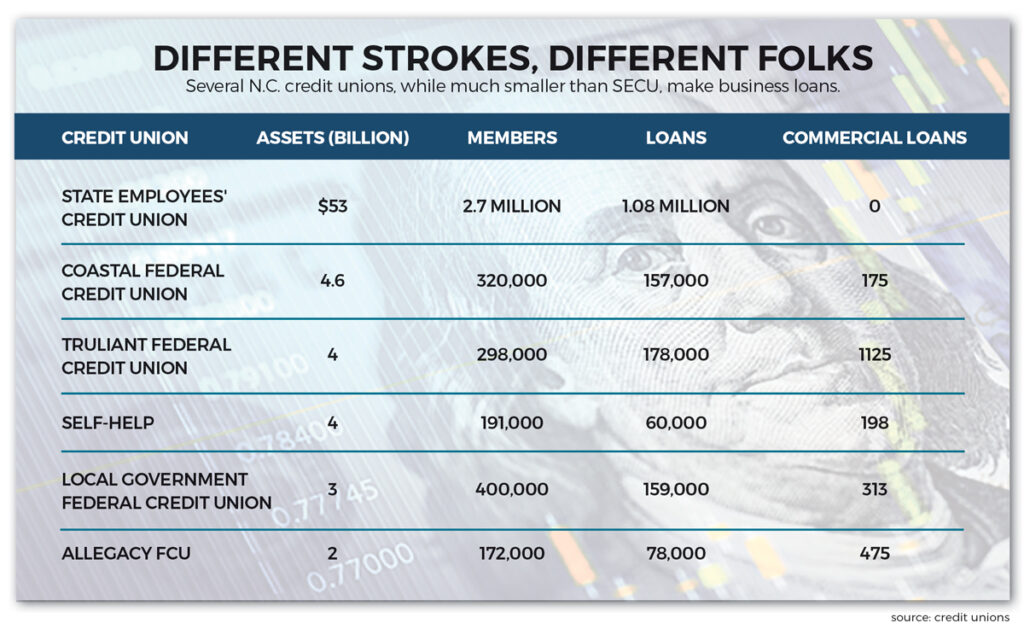

Another new plan: SECU wants to make business loans to members with needs such as expanding their office space. While some N.C. peers issue such loans, SECU has not.

Hayes notes that he regularly hears from advisory board members and branch workers about customer demand for small business credit. It’s particularly critical in rural areas that have been increasingly abandoned by N.C. banks, he says. SECU, with 273 offices in 100 counties, is the sole financial center in several N.C. small towns.

The shift has received limited notice because it’s occurring gradually and credit union leaders downplay the significance. SECU eschews publicity and media advertising. Its marketing mostly involves more than $20 million in annual philanthropy from its affiliated foundation, which is funded by $1-a-month fees paid by members.

SECU is undergoing a “pivot” more than a transformation, Hayes says during an interview at the company’s downtown Raleigh headquarters. (In subsequent discussions, two board members rejected the term “pivot” as overstating what’s happening.)

Hayes compares the credit union’s potential challenge with a famous collapsed video-rental chain.

“We need to be paying attention, so we don’t become irrelevant and frankly, the next Blockbuster that refused to ever budge on their direction, and became irrelevant and went away,” Hayes says. “We’re about wanting to serve our members for another 85 years.”

Board chair Chris Ayers — who is not

related to Chris Ayer — says, “this is more about evolving our products

and services to meet the evolving needs of our members, who are more

diverse than ever before.” He is the executive director of the N.C. Utilities

Commission’s Public Staff.

What’s happening at SECU is much more than an evolution of products and services, says Chip Filson, a credit-union industry consultant and former regulator who has tracked the N.C. enterprise for many years.

“The fundamental premise of State Employees’ has been that there is a need for institutions that are not-for-profit that focus on serving those who are less advantaged, and that’s become even more urgent,” he says. SECU looks to be following the path of other large credit unions and commercial banks that are seeking those with “the most assets, the biggest mortgages, the highest-paying jobs and often much stronger credit.”

“SECU was the most notable exception to this strategy,” he adds. “Jim Hayes is trying to bring it into the mainstream of credit-union thinking and direction today.”

DISSIDENT VOICES

What’s happening at SECU would likely be under the radar except for a 15-minute speech at the Oct. 11 annual meeting by the most influential executive in the institution’s history.

Jim Blaine was CEO from 1979 to 2016 as its assets grew from $335 million to $30 billion. Since departing, he’s hung out at his farm near Oxford harvesting eggs, raising daffodils and staying out of the public eye. (His son, Jim Blaine Jr., is a Raleigh political consultant and former chief of staff to N.C. State Senator Phil Berger.)

The elder Blaine read a statement describing the credit union’s history and posed seven questions. He then made motions asking directors to respond to his queries by meeting with advisory boards and issuing a strategic plan to explain “a new culture and new direction for SECU.” The motions passed.

The credit union followed up with three meetings in November and December in Greensboro attended by more than 500 members and employees. Hayes, Ayers and other leaders discussed Blaine’s questions and SECU strategies, taking written questions but not allowing debate. A videotape and strategic plan was delivered in early January.

At the meetings, Hayes said SECU planned to start using credit scores in loan decision-making by February. The business lending effort would probably launch in early 2024, he said. He repeated those dates in later interviews. On Jan. 17, a credit union spokesperson said the timeline is now “in the next few years.”

The elder Blaine says he showed up unannounced at the annual meeting because several former colleagues had alerted him to the pending changes. He contends risk-based lending will hurt most members financially and diminish SECU’s unique culture.

During Blaine’s tenure, SECU operated in direct opposition to many conventions of credit unions, much less commercial banks. Loan and deposit rates were level for members no matter their credit rating, while its home loans include terms that don’t conform with rules set by quasi-government agencies such as Fannie Mae.

The latter strategy was unpopular with regulators, but the credit union’s size and financial performance enabled it to push back effectively, says an N.C. credit-union president, who asked not to be named. The approach saves many members’ money and helps SECU develop a distinctive edge, he adds.

Blaine also rejected pleas by colleagues and board members to make business loans. He added a tax-preparation service and low-interest salary-advance loans, undercutting H&R Block and payday lenders. (Hayes cancelled the tax-prep program, noting it hurt customer service at branches during tax season.) SECU started life insurance, property management and investment units.

SECU also almost exclusively promoted employees internally. Blaine’s successor, Mike Lord, was SECU’s chief financial officer for more than 30 years. During his tenure from 2016-21, deposit growth accelerated, stoked by government stimulus checks delivered during the pandemic.

Under Lord, the credit union stepped up its technology spending, opening data centers in the Triangle and Charlotte areas that entailed more than $70 million. SECU chose to build and operate its own centers rather than outsource the work, which tech leader Ayer says showed the board’s trust in the staff.

Behind the scenes, however, the board was itching for C-suite change. Seven of 11 directors weren’t on the board when Blaine was CEO. The newcomers, who have influenced a new direction, include state government executives such as Ayers; Alice Garland, who ran the state lottery; Mark Fleming, a former lobbyist for the UNC System; and former state health care executive Mona Moon.

Key issues among board members, says Ayers, are concerns that SECU’s technology isn’t competitive and loan volume lags other financial-services companies that provide better terms for home and car loans.

“When you see members going to other financial institutions because the products they offer are more convenient versus the products we use here, simply because the technology is still catching up, that’s a concern for us,” Ayers says. “That means we aren’t serving our members to the fullest extent possible.”

At the Greensboro meetings, Hayes decried the state of SECU’s technology, noting a reliance on a base operating system installed in 1983. “What were you doing in 1983,” he asked.

Lord says he agreed with directors that SECU should have moved quicker to provide customers with a mobile app, an issue cited by Hayes and Ayers. But the former CEO notes the overall tech strategy received consistent praise. “Our moblie app was late, but it turned out very well,” he says. “I was there for 46 years and we experienced tremendous progress in our technology. All we ever did was change.”

In July 2021, SECU’s board hired Hayes as CEO on a 6-5 vote, according to several people familiar with the decision. At least four internal candidates sought the job, including two executives who remain at the credit union.

Hayes is a California native who had spent nearly 11 years as CEO of a $2.2 billion federal credit union that mainly serves the Andrews Air Force Base in suburban Washington, D.C. He had worked from 2003 to 2010 at the San Diego-based WesCorp corporate credit union, which was taken over by regulators in 2009 and dissolved in 2012 because of soured housing-related investments. He previously worked as a regulator for federal agencies overseeing credit unions and thrifts.

Hayes’ technology expertise and diverse experience impressed the board, former chair Bob Brinson says. The new CEO was open to change, but also respects SECU’s success, tradition and senior staff, Brinson adds.

Lord says he planned to stick around SECU briefly to assist Hayes in the transition. “It’s a $50 billion enterprise, and there are issues that need to be explained.” But he left after a few days, concluding his input wasn’t desired.

Chris Ayer, who led an IT group of more than 500 staffers, left several weeks later. Hayes emphasized the pace of technological change needed to accelerate, though Ayer says he was unclear about the CEO’s specific concerns and sensed it was time to leave.

Hayes says Ayer’s departure was not forced. “I don’t know why he left. He never told me.” Joshua Bomba, a former First Citizens Bank executive hired by Lord in 2021 to lead digital banking, was promoted to chief technology officer.

Hayes’ eight senior executives now include four long-term SECU staffers and four relative newcomers, including Bomba. Of the 10 highest-paid executives in 2020, five have retired and two are in Hayes’ top team: CFO Rex Spivey and COO Leigh Brady.

Hayes is creating a more transparent culture and making SECU a better place to work, says Brady, a 35-year employee who oversees branches, contact centers and the foundation. He’s expanded health plan offerings, added parental and bereavement leaves and floating holidays. He also relaxed a dress code requiring that men wear ties and sport coats at the branches.

“We’ve had good benefits, but they could have been better,” she says. “Jim has created a culture of having an open door. That hasn’t always been there at SECU.”

Dissension over SECU’s changes largely centers over so-called tier-based lending and small business loans. Credit-union leaders have discussed for years whether to offer different interest rates depending on a member’s financial standing. No one else in U.S. finance employs the “everyone-pays-the-same rate” strategy.

But SECU’s board thinks too many members with strong credit ratings are borrowing from rivals that offer better rates. “After a great board meeting” on Feb. 22, 2022, it okayed risk-based pricing for lending, Hayes said in an email two days later to all staffers.

“Only 10% of our members with A and B credit were borrowing from us,” Hayes says in an interview, referring to the industry practice of grading consumers by credit score, from A to E. “We need to be able to price loans that will bring some of the more higher-credit quality borrowers back into SECU.”

Over the last five years, SECU’s loan growth has been slightly lower than other U.S. credit unions with $10 billion in assets. The difference widened to more than 1 percentage point in late 2022. A higher percentage of SECU’s customers have home loans than its peers, but fewer have auto loans and credit cards.

Hayes acknowledges that SECU’s lending appeals to members with “C, D & E” credit scores, ranging from 530 to 660. His plan is to offer a more narrow band of rates so that members will still pay less than at other institutions. “We tend to lend a lot lower than our peers, and we’re going to continue to lend that deep.”

The math behind tier-based lending doesn’t match SECU’s mission of providing affordable rates to rank-and-file state employees earning $40,000 to $70,000 annually, Lord says. More than 60% of SECU’s existing borrowers will pay higher interest rates — often 2 percentage points or more — once the new pricing structure takes effect, he estimated in a December email to Hayes and board members.

Given SECU’s financial strength, “No select group needs to bear the weight of substantially higher loan interest rates,” he wrote. He says he didn’t receive a response.

“Teachers and state employees are the core membership, and they aren’t rich folks,” Lord says. “How is it better for the majority of our borrowing members to pay higher rates than they could obtain today.”

Asked about Lord’s estimates, Hayes notes that everyone is paying higher interest because of rising inflation.

Ayers says the most common question he receives from coworkers, friends and family is why SECU “isn’t competitive on loan rates. They say I love my credit union, I put my deposits there, but you aren’t competitive on mortgages or other loan rates.”

Such concerns didn’t bother Blaine or Lord because SECU’s focus resulted in decades of consistent, safe growth. If members could find better rates elsewhere, that was viewed as positive, Blaine says. Competitors’ lower rates often hide higher costs, he says, such as auto dealers offering a teaser interest rate while raising the sales price of cars.

As CEO, Lord regularly emphasized SECU’s preference for local staffers making credit decisions rather than centralizing authority in Raleigh. Knowing customers individually worked for SECU, which has traditionally charged off less debt than most industry rivals that rely heavily on credit scores, he says.

The local focus paid off in the 2008-09 recession when SECU’s mortgage assistance program enabled about 3,000 members to work out payment plans and avoid foreclosures. “We could do this because we were local, did not sell members’ loans and had full control to help them,” Blaine says.

SECU made about 298,000 loans to members with “D” credit scores of 540 to 599 as of November 2021, totaling $2.1 billion, a company report notes. The annualized loss on those loans averages 1.2%, suggesting that about 1 of every 100 “high-risk” borrowers pay about 99% of their debt.

The credit union also had about 480,000 borrowers with “A” and “B” credit scores of 660 to 850, totaling $15.3 billion in loans. Only about 0.10% was charged off.

Using risk-based lending, SECU will most likely raise the interest rate for “D” borrowers and reduce it for “A” and “B” customers — though about 99 of 100 SECU members pay their bills in each category.

Brinson, a retired state government IT executive who has been a director since 2007, says he long believed that every member should get the same rate. “I’ve come to the realization that we are not giving fair treatment to our high-credit customers,” he says. “But the board is very watchful about this issue.”

STRONG PUSHBACK?

Whether the change will spark significant opposition is being watched by state leaders. “SECU was the single best credit union in America, serving working-class people in every county in North Carolina,” says Martin Eakes, who cofounded the Durham-based Self Help Credit Union. “We will have to wait and see if it maintains that reputation. Some of the changes SECU has made in the last year are not good for North Carolina.”

At the State Employees Association of North Carolina, Executive Director Ardis Watkins says the credit union “is critical to the financial success of state employees.” Risk-based lending “eliminates loan options for many state employees who may not make enough or don’t have money to buy a car or a home. It sounds to me like they are positioning the credit union to be a bank.”

The North Carolina Bankers Association has had a historically frosty relationship with SECU over its tax-exempt status. The bankers oppose allowing SECU to make commercial loans, says counsel Nathan Batts.

Credit unions “are supposed to focus on serving people of modest means who share a common bond, like an occupation or association, or to groups within a well-defined community,” he says. “The whole premise of business lending by large credit unions can quickly run counter to that focus.”

SECU is “not trying to become a commercial lender like BofA or Chase,” Hayes says. “Other credit unions are doing small-business lending like we will be doing with our members.”

Darrin McNeill is the owner of Serenity Therapeutic Services, a 150-employee mental health services company in Raeford and a 33-year SECU member. He says he’s disappointed that SECU hasn’t made business loans. “I feel I’ve never received the type of service from [other lenders] as I have from SECU.”

SECU officials insist the core mission is unchanged, and a better credit union is emerging. A test may come at the fall annual meeting if dissidents nominate candidates for the three or four board seats that will be up for election. But policies of credit union leaders are rarely rejected because it’s so hard to organize rank-and-file members, consultant Filson says.

Given SECU’s historic importance, “the outcome will have national consequences for the future direction of credit unions.”

(The online version of this story includes a comment by Darrin McNeill of Raeford.)

A PENDING BATTLE

A shifting strategy at State Employees’ Credit Union comes at a prime time for the credit union industry. The industry’s loans soared 19% during the year ended Sept. 30, according to the National Credit Union Association.

Credit unions are also consolidating. The number of institutions with at least $1 billion in assets increased from 395 in mid-2021 to 414 a year later.They made up about 75% of industry assets of $2.1 trillion. The U.S. has about 4,800 credit unions.

Reflecting the industry’s financial strength, U.S. credit unions announced 16 purchases of commercial banks in 2022, matching a record set in 2019, according to the Banking Dive newsletter.

North Carolina credit unions want some changes in state law governing their operations, says Dan Schline, CEO of the Carolinas Credit Union League. Statutes haven’t been “modernized” since the mid-1970s, he says.

It’s not clear what lawmakers will be debating. But the industry favors allowing credit unions in economically depressed counties to more easily add members. Banks have closed many offices in rural areas of North Carolina, creating more opportunities for credit unions to serve those areas.

There’s also talk of allowing N.C. credit unions to make loans to minority- and women-owned businesses throughout the state, even if the owners are not members.

North Carolina bankers oppose allowing credit unions to expand their “field of membership” and add lending powers. They are nervous that SECU supports the potential changes — the Raleigh-based institution’s massive network dwarfs other N.C. credit unions.

“This is a thinly veiled attempt to change the credit union charter while dodging something that would actually be meaningful — requiring credit unions to comply with the federal Community Reinvestment Act,” says Nathan Batts, counsel for the N.C. Bankers Association. The CRA requires banks to reports statistics to fair lending and investing in underserved communities. ■

No comments:

Post a Comment